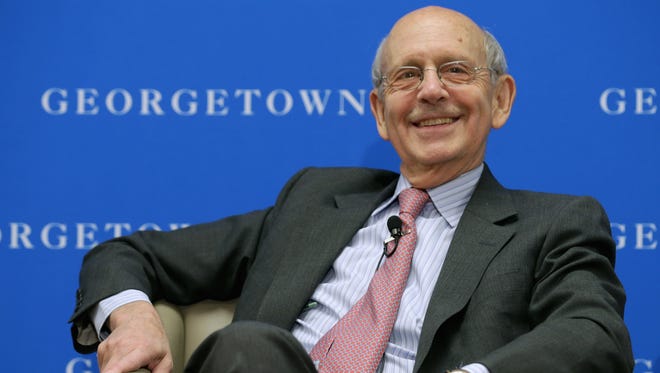

After 20 years, Breyer is high court's raging pragmatist

WASHINGTON -- When Supreme Court Justice Stephen Breyer gathered scores of former law clerks for a reunion to celebrate his two decades on the bench, he was toasted as an undying believer in the U.S. system of government.

Whether Breyer, who marks his 20th anniversary on the high court this week, was in the majority or dissenting from the conservative court's decisions, "he was always optimistic," recalled Michael Leiter, who clerked for Breyer and is former director of the National Counterterrorism Center. "He brought a level of optimism about the positive change we could make."

That joie de vivre has defined the 75-year-old Proust scholar's career from the time he worked in the political trenches for Sen. Edward Kennedy to today's service on an often deeply divided high court.

Perhaps more than anyone in Washington, Stephen Gerald Breyer is a believer in the democratic system – even one that seems as frequently dysfunctional as his own. His boyish buoyancy is born of experience in all three branches of government.

"He is unapologetically pragmatic in thinking that it's the court's job to help make government work for real people," says Kevin Russell, a former Breyer law clerk who argues frequently before the high court. "He thinks we're all kind of in this together."

Not a doctrinaire liberal like some of his predecessors and colleagues on the court's left, Breyer has proved harder to categorize. More than any other justice but Anthony Kennedy on the current court, the former Harvard Law School professor a fan of compromise.

"If you read Breyer's opinions, one constant strain is an attempt to come up with the gray to balance the black and the white," says Kenneth Feinberg, the acclaimed mediator and administrator of victims' compensation funds, who has been a close friend since the two served on the Senate Judiciary Committee in the 1970s. "He is extremely practical. He doesn't have an overriding constitutional philosophy."

Thus it was that in a complex antitrust case last year involving alleged collusion among drug companies, Breyer's majority opinion endorsed neither side but a "rule of reason." In this year's majority ruling against an Internet start-up's effort to avoid TV network ownership rights, he said the Copyright Act must be read not literally but "in light of its purpose."

And in his majority opinion last month striking down so-called "recess appointments" President Obama made while the Senate was holding pro-forma sessions every three days, Breyer refused to go further and deny almost all constitutional protection for the practice.

"There is a great deal of history to consider here. Presidents have made recess appointments since the beginning of the republic," he wrote. "We must hesitate to upset the compromises and working arrangements that the elected branches of government themselves have reached."

Adam Winkler, a constitutional law expert at UCLA School of Law, says the landmark ruling "embraces a progressive vision of the Constitution, and that may be Breyer's greatest legacy."

Others see it as judicial activism run amok. While the judgment against Obama's appointments was 9-0, its reasoning was 5-4; the court's most conservative justices argued that the Constitution's precise language invalidated virtually all recess appointments. Justice Antonin Scalia, Breyer's frequent opponent, complained that his rules on congressional recesses "have no basis whatsoever in the Constitution; they are just made up."

DEFERRING TO CONGRESS

In speeches to law schools and think tanks, Breyer likes to point out how unified the high court can be, despite the presence of extreme conservatives and liberals. As the fifth of the current justices to reach the 20-year mark – something the court has never had before – he likely played a role in the past term's unusual degree of unanimity. He declined to be interviewed for this article.

"He's a profoundly decent person," says Neal Katyal, a former acting solicitor general and Breyer law clerk. "On the court, when you're sitting with the same people for decades, I do think that ultimately matters."

Breyer has sided with the court's conservatives in some major cases, such as last year's ruling that police can take DNA swabs from suspects after their arrests to enter into a database of unsolved crimes.

Just this year, he sided with conservatives in upholding Michigan's constitutional amendment banning affirmative action in university admissions. While approving the use of racial preferences at colleges that allow it, he said the decision can be left up to the voters.

"Just as this principle strongly supports the right of the people, or their elected representatives, to adopt race-conscious policies for reasons of inclusion, so must it give them the right to vote not to do so," Breyer wrote.

That type of deference to police, states and voters also applies to Congress. On the current court, Breyer, an expert on administrative law, has been the justice least inclined to strike down legislative actions.

He spent much of his early career in Washington, working in all three branches: as a clerk for Supreme Court Justice Arthur Goldberg, at the Justice Department and U.S. Sentencing Commission, and as counsel to the Senate Judiciary Committee. There he earned a reputation for bipartisanship, helping to craft legislation deregulating the airline industry.

That reputation helped advance Breyer's career. In 1980, before leaving office, President Jimmy Carter named Breyer to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the First Circuit. Republicans could have let the nomination languish following Ronald Reagan's election, but they allowed Breyer to be confirmed. He served 14 years in Boston, the last four as chief judge.

As President Clinton's second nominee to the Supreme Court following Ruth Bader Ginsburg in 1993, Breyer not only has opposed the rigid adherence to the words of the Constitution known as originalism – he wrote a book putting forth an alternative. In Active Liberty: Interpreting our Democratic Constitution, he said judges also should consider the Framers' intentions and the practical consequences of their decisions.

Having served most of his tenure on a closely divided court that leaned to the right, Breyer has grown accustomed to small victories and bigger defeats.

His willingness to dissent was evident his first year on the court, when he wrote the principal dissent against Chief Justice William Rehnquist's ruling that Congress lacked the power to ban guns in schools under the principle of interstate commerce. "In today's economic world, gun-related violence near the classroom makes a significant difference to our economic, as well as our social, well being," he said.

A decade later, Breyer cited the court's landmark Brown v. Board of Education decision in a scathing dissent against a 5-4 ruling striking down Seattle's school desegregation plan.

"It distorts precedent, it misapplies the relevant constitutional principles, it announces legal rules that will obstruct efforts by state and local governments to deal effectively with the growing resegregation of public schools, it threatens to substitute for present calm a disruptive round of race-related litigation, and it undermines Brown's promise of integrated primary and secondary education that local communities have sought to make a reality," he wrote.

'HOW A FINE MIND WORKS'

Professorial and convivial at the same time, Breyer sprinkles his public appearances with references to history, foreign affairs and the classics. During a recent speech on international law, he cited James Madison, Louis XIV, Cicero, the Magna Carta, Camus, Napolean, the Nazis, Burkina Faso, Immanuel Kant and Alexander Hamilton.

"He's not just a great jurist," said Strobe Talbott, the Brookings Institution president, upon introducing Breyer at that event. "He is also a great teacher, so be prepared to learn something over the next hour and a half -- not just about the law, but also about how a fine mind works."

Breyer also is known for his writing skills. Retired justice John Paul Stevens recently called him one of the two best writers in the federal court system today, along with Richard Posner of the 7th Circuit Court of Appeals.

Despite those accolades, Breyer has spent 20 years on the high court in relative obscurity. He labored as the junior justice – the one responsible for taking notes and answering the door during private conferences – for a near-record 11½ years before Samuel Alito was confirmed in 2006. He is the least known of all nine justices -– recognized by just 3% of Americans in a recent Findlaw.com poll.

"He's not writing for the media. He's not writing for frills. He's not writing for one-liners," says Pratik Shah, a frequent Supreme Court litigator and another of Breyer's former law clerks.

During oral arguments, however, Breyer is the most demonstrative justice on the bench, often waving his arms for emphasis. He also asks the most long-winded questions, often concluding with "OK, what's the answer?" or "Now, why am I wrong?"

Despite calls from some liberals that he step down before Obama's term ends to give the Democratic president a chance to replace him, Breyer appears to be having far too much fun to retire.

"There's nobody I know who enjoys his work more than Justice Breyer," Feinberg says. "I think he will stay on that court as long as he's capable of doing the work."